NEW ADDRESS FOR MEMBERS GREYFORUMS.ORG

-

Posts

124 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Gallery

Everything posted by MKparrot

-

I have no idea why Greys pull and dump their food bowls:confused: They probably do it just for fun:) My Poly used to drop the bowl in the cage when he was two years old. After two weeks of his "enjoyment" I decided to stop it. I have placed bigger and heavier stainless steel bowls so Poly had to put huge efforts to pull them out. Then, after he had pulled and dumped the bowls I would have not lift them and would not filled with food again. I would left them dumped for 2-3 hours before placing them back and refiling with food. For two weeks he quit this annoying habit. I guess he considered that it is not worth to get tired in pulling bowls that only brings him to wait for a food for 3 hours.

-

Picture No. 3 is GREAT! I like it. And picture No. 4 make me jealous - my Poly would never take a bath that way.

-

Greys do not cough i.e. they can not cough, so don't worry about it. However, it they feel cold - they sneeze, and it sounds almost same as humans. My Poly randomly coughs and when I ask him - "Poly are you ill" - he starts to cough

-

After "Parrots in art" now we have "A Parrot Christmas poem"... This Forum seems to have more and more refinement. Bravo!

-

Have you checked with the doctor that it is dander that caused your problem. Maybe (I am hoping so much) it something else? I am sorry to hear that Gracie will have to leave you... I admire your love and passion for Gracie ! I really DO.

-

Nickelback's Rock star???? I was expecting Miley Cyrus :)

-

Yeah........ wright and for sure...it was Dayo you were talking about :rolleyes:

-

This is the post of the week... I like it, I like it a lot...it made my day:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D:D 10 out of 10 points. Maybe moderators should think over the idea to introduce аacknowledgment for the "funniest & best good mood post of the week/month and thread of the week/month"

-

...I am terrible dancer...Poly would probably freak out if he see me dancing...not to mention my singing that is even worst :D:D

-

One walnut, twice a week, is a nice addition to Grey's diet. I give my Poly occasionally whole raw walnut (with shell- thoroughly washed) and he enjoys breaking it and eating it peace by peace. Many people use them as rewards in training sessions, they are great motivators. Be moderate with walnuts - they are high in oil and fat. I have not heard of anyone roasting them unless for cake preparation

-

And now for something completely different - Parrots in art

MKparrot replied to MKparrot's topic in The GREY Lounge

-

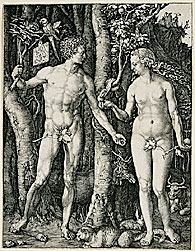

And now, for something completely different! (to paraphrase Monty Python's famous catchphrase ) Parrots (and parrot lowers) are not all about training, feeding, clipping, taming and poop cleaning:rolleyes:. Parots, ladies and gentlemen, are also about art. Few years ago “The Parrot in Art from Durer to Elizabeth Butterworth” exhibition was held in Birmingham UK . Strictly speaking, this discursive exploration of the parrot’s place in the history of art begins not with Durer but a little earlier. Its first image is a slightly foxed, battered but moving little woodcut, created by an unknown German artist in the third quarter of the fifteenth century. The subject of the picture is the Christ child and on his lap he holds a parrot – to be specific, a Long-tailed Green Parakeet – cradling it in such a way that its head brushes his cheek. It seems that the print was originally designed as a New Year’s greeting card. The image of Christ and the prophetic parrot – bearer of good news about the future – was intended to bring a message of hope for the year to come. Nearby, Martin Schongauer’s late fifteenth-century engraving of The Virgin with a Parrot, introduces the creature into a scene of the Madonna and Child. Seated by a window, the Virgin holds open a book with one hand while supporting the infant Jesus with another. He plays with the eponymous parrot, which inclines its head towards him with appropriate deference. As well as securing a walk-on part in images of the Holy Family, the parrot also migrated into the Garden of Eden. The parrot appears in Durer’s great early sixteenth-century engraving of The Fall of Man. Perched just above the figure of Adam, who looks questioningly towards the Eve, as she proffers him an apple, Durer’s parrot is implicitly contrasted with the devious serpent, twined around the trunk of the Tree of Knowledge. The benevolent bird looks away from the scene of temptation, as if pained by the sight of the Fall of Man. The sprig of mountain ash which supports the parrot also supports a tablet of wood bearing a prominent inscription that declares “Albrecht Durer of Nuremberg made this 1504”. The particular bird that modelled for the Eden parrot may have been actually owned by the painter. Durer made two other drawings of the same creature – an Alexandrine or Ring-necked Parakeet – in the early years of the sixteenth century. One of the revelations of this show, in fact, is just how many artists have owned parrots – Reynolds, Edward Lear, William Nicholson. Perhaps it is partly because the birds are nature’s equivalent of a palette, loaded with colour. The exhibition “The Parrot in Art from Durer to Elizabeth Butterworth” was the brainchild of Richard Verdi, Director of the Barber Institute, not only a distinguished art historian but a lifelong parrot aficionado. He claimed that the earliest parrot brought to Europe was a member of the same species as the bird Durer may have owned. He stated that the first parrots imported into Europe came from India and among their earliest recorded owners was Macedonian Conqueror Alexander the great, who, after conquering the Persian Empire, drove his army to the Punjab in 327 BC. On his return he brought back with him a green parrot with a rose-pink collar and blue cheeks that has subsequently come to bear his name: the Alexandrine Parakeet. The parrot was destined from then on to enjoy a favoured status in the ancient world. Aristotle, Pliny and Apuleius wrote at length about it, focussing upon its intelligence and powers of speech. It also forms the subject of one of Aesop’s Fables and of an elegy by Ovid of c. 15 BC, which mourns the passing of a beloved parrot nearly two millennia before Monty Python’s dead parrot sketch As it moved into the later Renaissance and beyond, Verdi’s exhibition increasingly explored parrots in the secular rather than sacred context. A prominent Blue-fronted Amazon parrot stands on the dinner table in the company of William Brooke, 10th Lord Cobham and His Family. The bird’s appearance here suggests the extent to which it had become a kind of status symbol among the European aristocracy – loved not only for its colour, exoticism and rarity, but also for its ability to inspire affection and mimic human behaviour. Less than half a century before Brooke had his portrait painted, the poet John Skelton had encapsulated the bird’s appeal among the royalty and aristocracy of the time: “With my beak bent, my little wanton eye, / My feathers fresh as is the emerald green, / About my neck a circulet like the rich ruby, / My little legs, my feet both feat and clean, / I am a minion to wait upon a queen.” In Holland too, parrots stood for status, becoming the avian equivalent of the tulip – brightly coloured, highly sought after and subtly symbolic of the reach and the spread of Dutch maritime trade and economic power. Jan Fyt’s mid-seventeenth century A Still Life with Fruit, Dead Game and a Parrot shows an African Grey Parrot . A Scarlet Macaw, occupies Jacob Fransz Van der Merck’s Still Life with Fruit and Parrot. Perched by the window in an interior so impossibly heaped with fruit and fabric and fine porcelain that it resembles a cornucopia, the bird’s splendid plumage is contrasted with the grey clouds of a Dutch evening sky. These are innocent parrots but later representations of the bird are fraught with erotic meaning. During the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the parrot became an image of sexual lust and longing. Wistful women alone in their boudoirs contemplate their pet parrots as they dream of their distant lovers. The most famous examples of the genre are by Manet, by Courbet, by Renoir. The exhibition also included two wonderful lesser known paintings: A Woman in a Red Jacket Feeding a Parrot, by the seventeenth-century painter from Leiden, Frans van Mieris the Elder; and Giambattista Tiepolo’s smouldering Young Woman with a Macaw, a capriccio executed by the greatest Venetian painter of the eighteenth century for Empress Elisabeth Petrovna of Russia. A blushing young lady, in décolletage so low-cut as to reveal her right breast, stares into space. The parrot she caresses looks out at the spectator with a sharp, proprietorial gaze. The exhibition also included, among much else, a fine Goya of superstitious fools treating a parrot as an oracle, as well as Edwin Landseer’s comically anthrophomorphised portrait of Queen Victoria’s favorite parrot, an ineffably superior Scarlet Macaw. It concluded with a number of breathtakingly acute and subtle natural history illustrations by the preeminent modern painter of parrots, Elizabeth Butterworth.

-

nice! I am very familiar with repetitive "What are you doing" . Every morning, after exchanging "good morning", Poly ask me "How are you" and than many times "what are you doing" and I have to answer every single time he is asking me, during my preparation to go to work.:)

-

My "broken English" caused funny association to you? :D:D sorry

-

Welcome to the Grey Family:)

-

I've read somewhere these days that wiggling the tongue is a sign of friendliness of Greys. When your Grey wiggles his tongue, he is showing that he likes you and wants to cuddle. My Poly does not wiggle his tongue often and I haven't checked the above mentioned theory. Do you have any experience with this?:confused:

-

Oooooooooo YES they do get angry and that is for sure.

-

Hypothesis is that Psittaciform diversity in South America and Australasia suggests that the order may have evolved in Gondwanaland, centered in Australasia. The scarcity of parrots in the fossil record, however, presents difficulties in supporting the hypothesis. A single 15 mm (0.6 in) fragment from a large lower bill, found in deposits from the Lance Creek Formation in Niobrara County, Wyoming, had been thought to be the oldest parrot fossil and is presumed to have originated from the Late Cretaceous period, which makes it about 70 Ma ( Ma = million years ago) Other studies suggest that this fossil is not from a bird, but from a caenagnathid theropod or a non-avian dinosaur with a birdlike beak. It is now generally assumed that the Psittaciformes, or their common ancestors with several related bird orders, were present somewhere in the world around the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (K-Pg extinction), some 66 Ma . If so, they probably had not evolved their morphological autapomorphies yet, but were generalised arboreal birds, roughly similar (though not necessarily closely related) to today's potoos orfrogmouths . Though these birds (Cypselomorphae) are a phylogenetically challenging group, they seem at least closer to the parrot ancestors than, for example, the modern aquatic birds. Europe is the origin of the first undeniable parrot fossils, which date from about 50 Ma. The climate there and then was tropical, consistent with the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Fossils assignable to Psittaciformes (though not yet the present-day parrots) date from slightly later in the Eocene, starting around 50 Ma. Several fairly complete skeletons of parrot-like birds have been found in England and Germany. The earliest records of modern parrots date to about 23–20 Ma and are also from Europe. Subsequently, the fossil record—again mainly from Europe—consists of bones clearly recognizable as belonging to parrots of modern type. The Southern Hemisphere does not have nearly as rich a fossil record for the period of interest as the Northern, and contains no known parrot-like remains earlier than the early to middleMiocene, around 20 Ma. At this point, however, is found the first unambiguous parrot fossil (as opposed to a parrot-like one), an upper jaw which is indistinguishable from that of modern cockatoos. So, everything related to modern parrots started in Europe and now-days we have no native parrots here !!! :mad: Isn't this pure irony????

-

My Poly always prefer roasted peanuts over raw It is one whole true that temperature of 175C (appx 350F) will kill the germs and peanut will be safe for use. Apart from this "be safe" aspect, it seems that roasted peanuts are even healthier to birds and human than raw. There is a study that shows that roasting peanuts magnifies their antioxidant power. Researchers at the ARS Market Quality and Handling Research Unit in North Carolina tested this concept by roasting peanuts to 362 degrees F for time periods ranging from one up to seventy-seven minutes. After the roasting process, the roasted peanuts were examined to determine the level of antioxidants they retained. The dark roasted peanuts had a greater concentration of antioxidant-rich phenols as well as higher concentrations of vitamin E. The researchers believe the heat used during the roasting process protects the vitamin E in roasted peanuts from being oxidized itself . Most people are surprised to learn that peanuts in general have more antioxidant power than many common fruits that are known for their antioxidant punch. These poly-phenol antioxidants are enhanced when peanuts are roasted. In addition, they're a good source of monounsaturated fats to help lower cholesterol and reduce the risk of heart disease. Unfortunately, there's some question as to whether the monounsaturated fats in peanuts break down under the high temperatures associated with roasting. Peanuts also have the distinction of being the nut with the highest protein content.

-

From what you described I assume that Dolly may be uncomfortable or stressed of your presence or of something that associates her with you. You might want to look if anything has recently changed with/on you or you have acted in some particular and unusual way that was way out of Dolly's daily routine, that could be stressing Dolly. It could also be something that has become sort of a compulsive behavior. If Dolly is under stress because of you, it is something that involves some investigation and correction. Mention it to your vet the next time you go in for a check up. Hope this helps

-

...yes, I see that it was raised back in 2007... I simply over-viewed that there is already a thread on this question... hope it hasn't substantially violated forum rules...

-

Today Grumpy PM-ed me on Teflon flu danger. I have investigated a little and was shocked from what I found. I suppose this question was raised / alerted before on the Forum, but I think it may be appropriate to reveal it again for those that are not aware of Teflon danger (i.e. parrot owners like me ). So, all the credits for this info / thread goes to Grupmy. Polymer fume fever or Fluoropolymer fever, also informally called Teflon flu, is an inhalation fever caused by the fumes released when Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, known under the trade name Teflon or T-Fall or else)) is heated to between 300 °C and 450 °C. When PTFE is heated above 450 °C the pyrolysis products are different and inhalation may cause acute lung injury. Symptoms are flu-like (chills, headaches and fevers) with chest tightness and mild cough. Onset occurs about 4 to 8 hours after exposure to the pyrolysis products of PTFE. The polymer fumes are especially harmful to certain birds whose breathing, optimized for rapidity, allows toxins which are excluded by human lungs. Fumes from Teflon in very high heat are fatal to parrots, as well as some other birds. If your bird is exposed to the toxic PTFE or PFOA fumes emitted by certain non-stick coatings like Teflon, it is likely to die an excruciating death as it suffocates in the fluids its lungs rapidly produce to protect themselves. The vast majority of birds die from acute edematous pneumonia before they reach the vet. Those with minor exposure that manage to survive suffer with lifelong health repercussions from the event.

-

Parrots can suffer hard attack!!!! It is a true and not a myth, but I was surprised to find out that there is such a thing as CPR (Cardiopulmonary resuscitation) for birds CPR can save a bird's life in the correct circumstances. CPR is much more likely to be effective if the bird has suffered from acute trauma, and conversely, it is unlikely to have a positive outcome if the bird is very debilitated and has been ill for a long period of time and the body finally gives out. The basics of CPR are the same, whether dealing with a human, dog or bird. The three things that are evaluated before initiating CPR are: breathing, airway and pulse. When you come across an unconscious person, you get close to the person to listen and feel for breathing. You can use the old mirror trick by holding a small compact mirror up to the nose of a person to look for condensation on the surface. You watch the chest for respirations and movement. Next, you open the mouth and look for any obstructions, and with a human (or dog) you can even sweep the mouth with your fingers to ensure that the airway is clear and nothing is blocking it. To open the airway, the head is tilted back. Next, you feel for a pulse and listen for a heartbeat. You can even place your ear against the chest to listen for the heartbeat if no stethoscope is available. If the patient is not breathing, and the airway is clear, rescue breathing is begun. If there is no respiration, the airway is clear and there is no pulse or heartbeat, then CPR is begun. If a bird is found unconscious, the same parameters are evaluated: respiration (looking for the breast rising and falling, see if the abdomen is rising and falling, as well), airway (open the beak and examine the oral cavity, clear if necessary with a finger or cotton-tipped applicator, taking care to not have a finger bitten) and heartbeat (since it would be difficult to find and evaluate a pulse on a bird, listen to the chest on either side of the keel bone for heartbeat, or use a stethoscope, if available). For those of you who need a brief anatomy lesson at this point, at the base of the tongue is the glottis, which is the opening of the airway. You may need to gently pull the tongue forward to visualize the opening of the windpipe. The heart is basically centrally located far beneath the breast muscles, and under the keel bone, almost midpoint along the length of the keelbone. There are nares (nostrils) at the base of the beak, either in the fleshy band called the cere or at the edge of the beak where feathers meet beak tissue. Once you have evaluated the unconscious bird, check for respirations and clear the airway. Check for a heartbeat. If there is no breathing but the bird still has a heartbeat, begin rescue breathing. While holding the bird's head in one hand and supporting the body in the other, tilt the patient slightly away from you. With your head turned a quarter turn to the right or left, begin respirations. For small birds, you can seal your lips around the beak and nares, and for large birds, seal your lips around the beak only, while placing the index finger over the nares. Take a breath and blow five quick breaths into the bird's beak. The strength of each puff of breath should be determined by the size of the bird; for a little bird, just small puffs are needed, but for larger birds, you will need to use more force to breathe air into the lungs and airsacs. This takes practice and some skill, to learn how much force is necessary to adequately inflate the lungs. Remember that birds breathe like a bellows, out and in, so look for a rising of the sternum with each breath. You can visualize this most easily where the sternum meets the abdomen. If the breast is not rising, then you are not getting enough air into the respiratory tract and you must recheck to ensure that the airway is open. If the breast is rising with each puff, then pause after five breaths and observe the bird to see if the bird has begun breathing on its own again. If it has not, then give two more puffs of breath and evaluate for breathing again. Don't forget to check periodically to ensure that the bird's heart is still beating. You will continue the two puffs, then checking to see if the bird is breathing and that the heart is still beating, either until the bird begins respiring on its own or until you can present the bird to your avian veterinarian or emergency clinic. If there is no respiration, the airway is clear and there is no heartbeat, or if the bird's heart stops beating while performing rescue breathing, then you will begin CPR. You will continue providing puffs of breath into the beak and add chest compressions. Birds have a very rapid heart rate when compared to humans and dogs, so you will attempt to provide the bird with 40-60 compressions per minute, based on the size of the bird. Placing one to three fingers on the keelbone (depending on the size of the bird, one finger for budgies, three for macaws), begin applying finger pressure to the keel bone, depressing the keel, which will in turn, compress the heart, moving blood through the tissues. As with performing rescue breathing, the amount of pressure necessary to depress the sternum adequately can be adjusted, based on the depth of sternal compression. The pattern will be five puffs of breath initially, followed by ten compressions, check the bird for heartbeat and breathing, then give two breaths, ten compressions, two breaths, ten more compressions, continuing in this manner for a minute. Have someone time this for you, if possible. At one minute, re-evaluate the bird for heartbeat and respiration. Continue providing CPR in this manner until the bird either recovers or is safely transferred to a veterinary clinic or emergency facility. If the bird begins breathing on its own it should be placed in a warm, quiet environment and you should then contact your avian veterinarian for instructions on what to do next. If this column has piqued your interest, please investigate CPR classes in your area, or perhaps ask your avian veterinarian if he or she will teach a small class for interested bird owners. It is best if you can practice CPR on a human dummy, a dog dummy or even a stuffed bird before you ever need to perform this on a live patient. NEVER attempt to practice avian CPR on a live, healthy pet bird!!! Once the bird has been delivered to the avian veterinarian, the bird will be re-evaluated and possibly intubated (meaning that a tube will be placed into the trachea or windpipe, or if necessary, an air sac breathing tube can be placed into an air sac, bypassing the windpipe, in certain situations). Once a breathing tube is in place, oxygen can be supplied to the bird via the tube. Certain medications can be administered to the bird either directly into the breathing tube or into a vein, if one is accessible, that can attempt to stimulate the heart, correct metabolic problems and stimulate breathing, as well. Your avian veterinarian will provide your best chance for stabilization and recovery. Hopefully, you will never need to use CPR but I thought it is worth knowing.

-

Yes, no Greys around us. In my country (Macedonia) we have mild sub-Mediterranean climate, but so far there is no feral parrots colonies. I believe it is the case all across the southern Europe.

-

Rainbow Lorikeet Feral colonies of Rainbow Lorikeet have been established in Perth, Western Australia and in Auckland, New Zealand. Eastern Rosella The Eastern Rosella has become naturalized in the North Island of New Zealand Rose-ringed Parakeet A sizeable population of naturalized Rose-ringed Parakeets (Psittacula krameri) exists in and around cities in England, the Netherlands, Belgium and western and southern Germany. The largest UK roost of these is thought to be in Esher, Surrey, numbering several thousand. Feral Rose-ringed Parakeets also occur in the United States, South Africa, Egypt( Resident, breeding all over Giza territory in june), Israel (with many seasonally present in Yarkon Park in North Tel Aviv), Lebanon, UAE and Oman. Other Also found in the United States are various naturalized Brotogeris a.k.a. White-winged Parrot and/or B. chiriri Yellow-chevroned Parakeet/Parrot. Brooklyn (in New York City), Chicago, Illinois, Austin, Texas and Miami, Florida are home to populations of Myiopsitta monachus (Monk aka Quaker Parakeet/Parrot). A population of naturalized Rose-collared (a.k.a. Peach-faced Lovebirds) (Agapornis roseicollis) is found in Tucson, Arizona. Several species, including Red-lored Parrots (Amazona autumnalis), Lilac-crowned Parrots (Amazona finschi) and Yellow-chevroned Parakeets (Brotogeris chiriri), have become well established in Southern California and a population of mainly Red-masked or Cherry-headed Parakeet/Conure, a female Mitred Parakeet/Conure and thus several inter-specific hybrids live in the area of Telegraph Hill in San Francisco, as depicted in the documentary The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill. In the greater San Francisco Bay Area, there are several populations of Red-masked Parakeet, including in Palo Alto and Sunnyvale. The Belmont Heights District in Long Beach, California is also known to have many different species of feral parrots which have become local icons to the citizens of the area. They are known for their loud and unique noises as well as their large communities. These parrots can be found roosting mostly on Ocean Boulevard between Livingston Drive and Redondo Avenue in palm trees. The San Gabriel Valley in California has a large, non-indigenous population of naturalized parrots. According to the "Parrot Project of Los Angeles", the parrots are of at least five species. Residents have come to enjoy the birds as part of their unique city's culture, and like other SoCal residents they have become "local icons" to the citizens there. Many theories surround the mystery of how the parrots landed in Pasadena and claimed the area as their own. A widely accepted story is that they were part of the stock that were set free for their survival from the large pet emporium at Simpson's Garden Town on East Colorado Boulevard, which burned down in 1959. Malibu, California has populations of Black hooded or Nanday Parakeets (Nandayus Nenday), Lilac Crowned Amazon parrots (Amazona Finschi), Red Crowned Amazon parrots (Amazona Viridigenalis), and Mitred Parakeets (Aratinga Mitrata). Lists of feral parrot species by continent North America • Mitred Parakeet • Blue-crowned Parakeet • Budgerigar • Blue-and-gold Macaw • Rose-ringed Parakeet • Monk Parakeet • Canary-winged Parakeet • Yellow-chevroned Parakeet • Peach-faced Lovebird • Spectacled Amazon • Red-lored Amazon • Blue-fronted Amazon • Lilac-crowned Amazon • Yellow-headed Amazon • Yellow-chevroned Parakeet • Red-masked Parakeet • Hybrid Mitred Parakeet • Hybrid Yellow-headed Amazon • Hybrid Red-crowned Amazon • Red-crowned Amazon • Nanday Parakeet South America • Jenday Conure • Monk Parakeet • Blue-fronted Amazon Europe • Alexandrine Parakeet • Rose-ringed Parakeet • Monk Parakeet • Fischer's Lovebird Africa • Rose-ringed Parakeet Middle East • Rose-ringed Parakeet New Zealand • Rainbow Lorikeet • Eastern Rosella • Crimson Rosella • Sulphur-crested Cockatoo • Galah Asia • Sulphur-crested Cockatoo • Yellow-crested Cockatoo